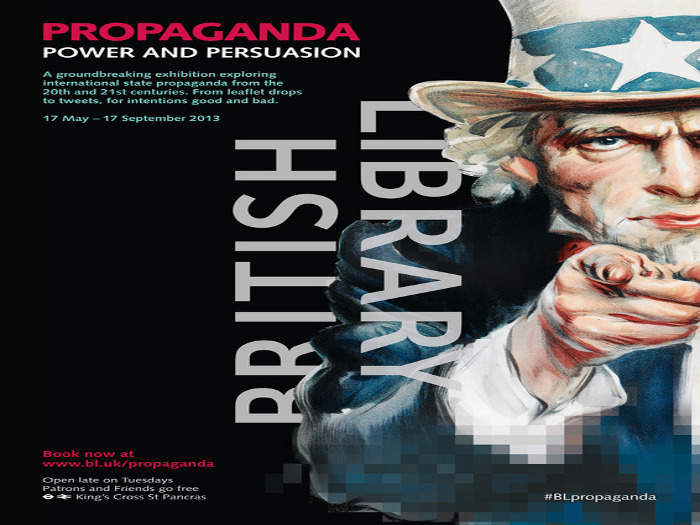

WALKING THROUGH THE British Library’s superb exhibition Propaganda: Power and Persuasion (on until 17 September), I was struck by what may seem to you rather an obvious thought. Propaganda is, in the way we use the term now, essentially state rhetoric. As a sort of ’ scholar’s not quite the word; let me say instead cheerleader of rhetoric ’ I found the show doubly interesting for that reason.

Here on every side are the great persuasive appeals first identified by Aristotle: ethos, pathos and logos. The first is the attempt to present a speaker (or a commercial brand, or a political leader) in a certain light; the second, the attempt to sway the emotions; the third (and very much the runt of the triplet; a last resort) the appeal to reason.

And though we may think of propaganda and art as opposites (one existing for itself, the other to further an end), it’s striking how their history has been entwined. So much of the pleasure and interest in the exhibition is visual rather than intellectual.

Here, for instance, are Mao Zedong and Lenin presented with the sort of totalising energy subsequent branding gurus would squander on Coca-Cola. Here is Kitchener, pointing his finger at YOU. Here is Napoleon holding Charlemagne’s sceptre, wreathed with laurels and caparisoned in his robes of state. Icons of gods and rulers — since first man dipped stick in puddle of woad — have been all about the transmission of power.

Art of Deception

Much as we now think of propaganda as being a natural monopoly of the state, it was not always thus. Think of all those Renaissance patrons, and remember that the first use of the word ‘propaganda’ was not by a government but by the Catholic church at the time of the Counter-Reformation, denoting ‘what was to be propagated’.

Portraiture — because it was almost by definition produced at the behest of the wealthy and politically influential — was an elaborately formal sort of boastful propaganda. It told you about the sitter’s place in the world, often much more than it told you what they actually looked like.

Look at all that bric-a-brac on the table in Holbein’s The Ambassadors — detailed self-puffery of a very conventional sort. The idea that Oliver Cromwell would commission a portrait and ask for ‘warts and all’ tells you something about what portraiture meant at that point (as well as how Cromwell intended to stake his ethos appeal).

In the public sector, portraiture-as-propaganda is still going strong, particularly in current or former totalitarianisms — witness the frequent photos of a topless Vladimir Putin wrestling bears or snapping crocodiles in half.

But in the private sector it has fallen into abeyance. God knows, the rich and powerful are still commissioning portraits. But by and large, because they are privately commissioned and privately held, and because private-sector power now operates by and large through back channels, they’re more by way of swanky family portraits than tools of domination.

Personal propaganda is different now. HNWs don’t call it propaganda: you call it ‘reputation management’. And you don’t do it with brush and canvas: you do it with keyboard and mouse, a silky telephone manner, a word in the right ear and, now and again, a thunderous legal letter.

I’m not sure it even deserves the name of propaganda. Tempting though it is to reach for a joke about ‘putting the PR in “propaganda”‘, one can’t envision with much satisfaction an annex to the BL’s exhibition containing waxworks of Tim Bell and Peter Carter-Ruck.

Pure Motives

There’s also the type you do with the chequebook. According to the Sunday Times Giving List, last year Britain’s wealthiest 231 people gave ’2.08 billion to charity. Is philanthropy a form of propaganda?

Snarks might say so, but then again, much as an HNW’s charitable giving might be geared to looking good, it could also be geared to making them tax-efficient or — we can admit the possibility — actually doing good. For the most part, in any case, charity donation is discreet and the HNW’s publicist works to keep him or her out of the papers rather than in them.

The visual bombast with which today’s HNW affirms his or her ethos appeal is a world away from monumental art. It has decayed into the oligarch’s showy yacht and the rap star’s bling, into not Waddesdon Manor but Trump Tower. And, perhaps, into Duchy Original biscuits, Prince Charles’s magnificent ethos appeal in butter, sugar and flour, each stamped with the Duchy’s crest.

Still, to see an artistic line that takes us through Holbein, Vermeer and Michelangelo replaced with a mega-yacht, to see the millions of coins stamped with the profile of Alexander the Great reinvented as lemon shortbread cookies in Waitrose, seems, at the very least, a bit of a missed opportunity.

Propaganda: Power and Persuasion runs at the British Library until 17 September 2013

Read more from Sam Leith

Read more from Column of the Week