I’ve been working on a book about children’s literature for the past year and a half or so, and I’ve noticed many things in the course of my research. The first is what an awful lot of death and violence there is in it: Peter Pan, not that you’d really know it from Walt Disney, is just fantastically bloodthirsty, to say nothing of Watership Down, The Jungle Book or even Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Another is how wonderfully free children’s authors are with the killing-off of parents: the sure way to be an orphan, it seems, is to be the protagonist of a children’s adventure story.

[See also: Could the British Library cyber-attack bridge a social divide?]

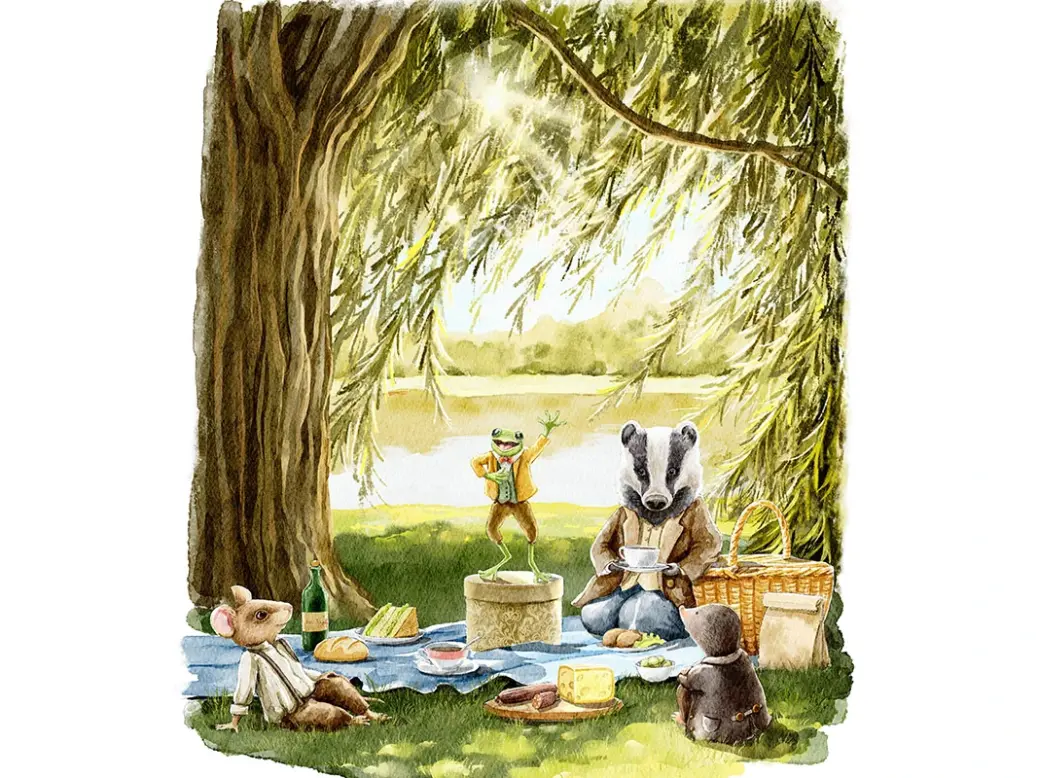

But the one that concerns us here, of all venues, is the question of money. In Victorian and Edwardian children’s literature, avuncular strangers are forever handing out shiny new coins to children. It seems to have been the done thing: pat them on the head, slip them a shilling. Even badgers do it: in The Wind in the Willows, for instance, Badger sees off some stray baby hedgehogs thus: ‘“Here, you two youngsters be off home to your mother,” said the Badger kindly. “I’ll send someone with you to show you the way. You won’t want any dinner today, I’ll be bound.” He gave them sixpence apiece and a pat on the head, and they went off with much respectful swinging of caps and touching of forelocks.’

Turning on a sixpence

Gosh, that’s a sea-change. Are there any readers who still remember strangers bestowing sixpences? Nowadays you might expect a nice grandma to enclose a fiver in the occasional letter or birthday card – or godparents sometimes to cough up on formal visits. Martin Amis wrote in Visiting Mrs Nabokov of how Philip Larkin used to tip little Mart and his brother Philip: ‘At first it was sixpence for Philip against threepence for Martin; years later it was tenpence against sixpence; later still it was a shilling against ninepence: always index-linked and carefully graded.’

[See also: Misery of the rich: Why the arts still portray the wealthy as sad and dysfunctional]

But nowadays, if your ten-year-old came home from the park and announced that a stranger had tousled his hair and given him a five-pound note, you’d as likely as not have the police out. Yet, going by the children’s literature of the past, donations from passing strangers or visitors to your parents were the main source of juvenile income: random pennies from heaven. (I’ve addressed the peculiar economics of tooth fairy transactions in a previous column for these pages, so I’ll confine myself to noting that forward-looking Norsemen were bribing their children for losing teeth as long ago as the poetic Edda, so I say ‘main’ rather than ‘only’.)

Pocket money or bust

At any rate, actual pocket money, much before the birth of the consumer age in the mid-20th century, didn’t really seem to be a thing. In fact, the very concept wasn’t popularised until the work of the parenting guru Sidonie Gruenberg, who argued in 1912 that a regular allowance would help children learn how to manage money. That’s very responsible, and you can see why it caught on. Indeed, we’re now in a position where not giving children pocket money will be seen – certainly by the children, but by most parents too – as a cruel deprivation.

Before the 20th century, children were in the odd position of earning money (whatever William Blake’s misgivings about the chimney sweep dodge, child labour was going on like billy-oh in this country until the 1933 Children and Young Person’s Act spoilt the fun) but being reliant on random handouts if they wanted any money to actually spend. What an inversion. These days the little sods won’t lift a finger to swell the family exchequer yet expect a regular stipend as of right.

[See also: Intellectual property: Why the best time to sell a classic author’s estate is yesterday]

My own kids, as soon as they get into double digits, are issued with a GoHenry card and a weekly pittance so they can wipe out their savings every week or two on bubble tea or some such nonsense. I try to link this dispensation to the performance of some basic chores – but it does stick in the craw a bit to feel you have to bribe your child to empty the dishwasher, and it becomes entirely pointless when they break a few quid’s worth of crockery in the process.

Bring back the strangers of children’s literature

So I like the sound of the old days. Regular pocket money may breed, or aspire to breed, the responsible husbandry of cash, and handouts from strangers may seem to encourage an irresponsible view of one’s prosperity as being blown hither and thither by the fickle winds of fate. But look at it another way: the prospect of getting ‘tips’ from strangers would encourage kids to be agreeable in public, and aren’t all our financial affairs, in some sense, in the hands of the fates?

Plus, the habit of donating a few shiny sixpences to passing tots would surely help foster a warm sense of community and make healthful visits to the park attractive to children more accustomed to goggling at the Xbox. And best of all, donations from strangers don’t deplete the parental bank account. It’s a custom I think worth reviving.

This column was first published in Spear’s issue 89.