If you stand at the Earl of Leicester’s front door at Holkham Hall and gaze out across the sweeping parkland you see a broad lake, grazing deer and, in the distance, a stone monument that owns the highest hilltop. It is the Leicester Monument, erected in 1848 and paid for by public subscription, dedicated to the life and work of the 1st Earl of Leicester, Thomas Coke (pronounced ‘Cook’).

As an MP for the county for five decades, a major landowner and the occupant of one of its finest houses – the Palladian marvel of Holkham Hall – he was celebrated in his day as ‘Coke of Norfolk’.

Today, however, he is remembered primarily as an agriculturalist, whose system of crop rotation was imposed on his tenants as well as his own estate. Indeed, he is credited with a major role in fostering the British agricultural revolution, which increased farming yields while reducing labour requirements, freeing workers for industry.

Now, nearly two centuries after the 1st earl’s death in 1842, the agricultural mantle which made his name is being taken on his great-great-great-great grandson.

That’s why I’m here, to meet the farmer Tom Coke, otherwise known as the 8th Earl of Leicester, to talk about his estate’s newly unveiled sustainability strategy, named ‘Wonder’.

But first I have a chance to explore. Our tour of the 25,000-acre estate begins along Holkham’s historic south avenue, which is more than a mile long, seemingly dead straight and serves as the ‘front door of the estate’ – that’s according to the man behind the wheel, Jake Fiennes. Pheasants scamper in the grassland and I spot a squat stationary brown mass. ‘A hare,’ declares Fiennes.

How Thomas Coke is making Holkham Hall more sustainable

Lord Leicester appointed Fiennes to be Holkham’s conservation director in 2018 – the year the estate adopted ‘regenerative agriculture’ methods.

Leicester tasked Fiennes with promoting environmental sustainability across the entire operation, which includes 5,000 acres of farmland and 2,000 acres of forestry.

Fiennes says that after the job was made public, Tom, as he calls the earl, got a deluge of phone calls from other large estates eager to find out what they had planned.

Even now, he says, ‘I’ve got the next generation of English landowners ringing me up on a regular basis: “Can we come and see you? Can you talk to my staff or my tenants?”’ Still, he says, ‘I don’t think there’s anyone else who does my job.’

Sheep and cattle stroll across the road as we approach the gatehouse and Fiennes slows the truck. The trees lining the historic avenue are being cut down and restocked.

‘A lot of the trees are in decline, so this is legacy stuff.’ It’s a ‘bold decision because my grandchildren will want to see this avenue. In another 200 years, if it wasn’t restocked it would disappear, so you’re maintaining this historic landscape.’

We stop outside the gatehouse, which is modelled on a triumphal arch, and look back: the long south avenue stretches into the distance to an obelisk, then cuts the great Palladian slab of Holkham Hall in half.

Beyond the house is the Leicester Monument. It’s all aligned. ‘‘That’s a pretty fucking impressive entrance,’ barks Fiennes as the engine falls silent.

If you consider that the English country house is arguably among this country’s greatest contributions to the visual arts, then Holkham – and this view – must rank in the highest order. It’s truly stunning.

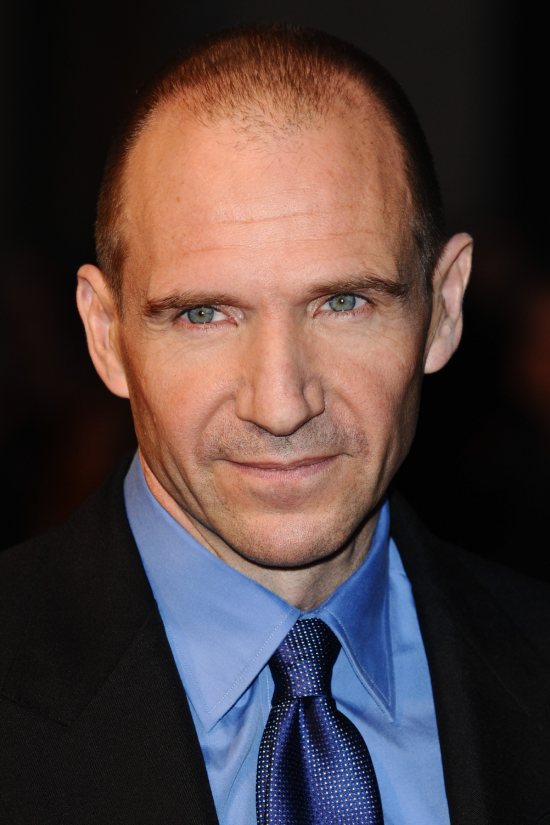

Imagine 200 years ago, he says… you’ve taken a carriage all the way from London to meet the great Coke of Norfolk and this is the sight that greets you. Fiennes is a brother of the actors Ralph and Joseph – but that’s not the reason he has himself garnered rather a lot of press attention of late, including a profile in The New Yorker, under the headline: ‘Can farming make a space for nature?’

Alongside his work at Holkham he advises civil servants and ministers, sits on the NFU region’s environmental committee, and is also hoping to attend COP26 in Glasgow to spread the word about restorative agriculture.

We pull over for a photo by a strip of bright yellow flowering crops which photographer Christopher Doyle, who has joined our sortie, identifies as rapeseed. ‘It’s not rape,’ says Fiennes. ‘It’s bird food.’

Turns out it’s a mixture of around ten different plants – including several types of kale and fennel – intended to provide food and shelter for a variety of other animals as well as the birds.

‘The natural world is not a monoculture, it’s multiple species,’ states Fiennes. As a result, when a field is planted with a multi-species crop as Holkham is now doing, it heals the soil and helps ‘catch all those nutrients, whether artificial, atmospheric or organic, and it prevents diffuse pollution through erosion, rain. It just makes the soil alive. The soil becomes alive because of the interactions between all the different parts.’

On our way to the 5,000-acre nature reserve, of which he is also director, Fiennes chuckles at the sight of a ‘harem of hen pheasants’ in the woodland.

Later he stops the car, reaches for his binoculars from the dashboard. ‘Hares,’ he announces. ‘Five of them.’

We continue and discuss the use of ‘headlands’, portions of land left to nature at the sides of each field. ‘We’ve lost 97 per cent of hay meadows in 70 years,’ he explains. ‘We can re-create hay meadows. That’s good for pollinators. We know that pollinators benefit food production – multifunctioning ecosystems benefit food production.’

Likewise, they’ve stopped mowing acres of the park. We turn a bend and his hand sweeps across the adjacent grassland: it’s ablaze with buttercups.

‘These flowers were never allowed to flower,’ he says. ‘They were constantly cut short.’ Understanding the importance of this interconnectedness puts us on a path to understanding ‘natural capital’, a key concept in the Holkham philosophy.

As we arrive at the nature reserve, we see a marshland landscape, peppered with questing wading birds and bordered with a long bank topped with lofty pines planted 200 years ago to protect the dunes from erosion. ‘Traditional accounting’ would only value the woodland according to its ‘sale value or income value’, says Fiennes. But at Holkham they look at things differently.

‘We’re now saying there’s a natural capital value,’ which is more important – and often greater – than the value that a traditional approach to accounting and estate management would reveal. If you chopped down the pines you might get £50,000 for the timber, he supposes, ‘but actually its natural capital value is probably 30 times that because it’s carbon, it’s biodiversity, it’s clean water – it’s all those public goods. A lot of the traditionalists are struggling with this, but it’s getting momentum.

The 8th Earl of Leicester aims to live up to his Dad’s impressive tenure

After the tour, Fiennes drops me off in the car park a short distance from the hall. At the porters’ door I’m greeted by the PA to the earl. She leads me along various corridors into a boardroom in the south-west wing of the house, and as she makes me a mug of coffee I can hear her trying to locate the earl over the radio.

The coffee arrives, and then so does the 8th Earl of Leicester, dressed in a pale purple shirt, blue cotton trousers and brown-to-burgundy Chelsea boots. It being the era of Covid, we don’t shake hands, but give each other an appraising nod – and sit.

Leicester, 55, speaks plainly and, despite being an Old Etonian, without the constricted vowels one might have expected from an earl 20 years ago.

He explains that at the heart of the Wonder sustainability strategy is a vision for the estate to be carbon negative by 2040, meaning it will take more carbon out of the atmosphere than it produces.

It will also pioneer ‘environmental gain’ along the way, promoting biodiversity, ecosystems and natural capital. The current earl took over the management of the estate from his father, the 7th earl, in 2008.

Since then, he says, he’s put a renewed focus into the management of Holkham’s forestry. ‘Dad said his only regret from his wonderful tenure – he did a cracking job – [was] he never employed a first-rate head forester,’ explains Leicester, who lavishes praise on Harry Wakefield, whom he appointed to that role in 2014. ‘Forestry, rather like the built environment, is one’s legacy.’

‘We are doing great things with the forestry,’ he continues, noting that the forestry operation ‘is making money’.

‘We are going to start calculating the cubic tonnage of timber in each wood, and if you manage your wood properly the cubic metreage will get bigger and bigger.’

That means the value of the holdings will rise – alongside the carbon storage capacity of the woodland. Meanwhile, the poorly managed woodland of 1970s heritage is being felled for use in one of the estate’s two biomass boilers, installed in 2012, generating electricity for the hall and the Victoria Inn, the estate’s pub. What goes around comes around.

***

The earl has also brought Holkham’s nature reserve back under ‘in-house’ management from Natural England, an environmental quango, but, perhaps most important of all he’s begun a quiet agricultural counter-revolution – one which rolls back 60 or more years of farming practice.

‘I don’t know if you’ve seen that really good film on Netflix, Kissing the Ground – it’s narrated by Woody Harrelson in his southern drawl? It features one of my heroes, Gabe Brown.’

The American farmer and pioneer of regenerative agriculture believes ‘it’s bad news having bare earth’, explains Leicester. Indeed, instead of ploughing the land after the harvest and leaving it fallow over winter before planting the next cash crop, the soil is sown in between with a ‘cover’ crop to keep the earth covered with life. This is something that Leicester has introduced at Holkham.

‘For all that time you’re sucking nitrogen out of the air – putting the nitrogen in the soil, so that’s free nitrogen fertiliser, which means that we are therefore spending less money on buying artificial nitrogen, which is arguably one of the most polluting substances in the world.’

In fact, artificial fertilisers are the biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, which accounts for around 10 per cent of global emissions. They have a bigger impact than the diesel that goes into the machinery, or the methane that emanates from livestock.

[See also: Emission Statement: How private jets are moving toward cleaner aviation fuel]

What’s more, artificial nitrogen fertilisers – invented by German scientists after the First World War – are a blunt instrument that can cause pollution to rivers and groundwater through run-off.

‘For every tonne of artificial nitrogen, three tonnes of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere,’ notes the peer. ‘So it’s a bad process.’

Leicester began using cover crops such as fodder radish in 2012 across a handful of fields at Holkham, but the practice has now been adopted across the estate. As well as drawing in free nitrogen and sucking up other goodies from the depths (‘imagine [the] long deep tap root,’ he says, burrowing his hand down, ‘going down into the soil – it’s breaking the soil up, it’s bringing nutrients and minerals up from the depths’), the cover crops also contribute to organic richness in another very direct way: through livestock.

‘All this rubbish from vegans saying we’ve got to stop eating meat,’ sighs Leicester. ‘We buy sheep in October from Bakewell market, bring them down here and fatten them on cover crop – it’s providing free forage and then you’ve got sheep muck as well.’

By the time the sheep have had their fill, the organic content of the soil – depleted by decades of chemical-fuelled monoculture – is on the rise, too. Reduced tilling also helps keep carbon locked into the ground, again reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but also improving soils’ abilities to retain water, thereby reducing flooding.

Despite the winter of 2020–21 being one of the wettest he remembers, Leicester notes that barely a handful out of ‘God knows how many fields’ comprising 5,700 acres of arable have flooded.

***

At Gabe Brown’s farm in North Dakota, 20 years of regenerative agriculture has led to crop yields 20–25 per cent higher than on average for the region, while the organic content of the soils has risen from 1.9 per cent to 6.1 per cent, increasing water penetration and reducing flooding.

In addition, as Fiennes showed me on our drive earlier, Holkham is inviting nature into its farmed realms – in a way that farmers haven’t for decades. I ask Leicester about the ‘headlands’ around the edges of his fields.

‘We want to attract those insects back so that all round the field we can attract predator insects like lacewings, ladybirds, hover flies, so that when the aphids descend on our fields the predator insects multiply,’ he says with enthusiasm.

In other words, he hopes to achieve through nature what most farmers currently achieve with insecticides. In 2019 the earl told his farm managers that, by 2030, he wanted to stop using all pesticides, insecticides, herbicides and fungicides. But Holkham is not ‘going organic’, says the earl, who concedes they’ll need to retain some artificial nitrogen on certain crops as well as some herbicides.

I ask if they might qualify as half or quarter organic instead? ‘I suppose… if our chemical fertiliser bill is half what it was before, you could say that we’re half organic,’ he ventures.

At the heart of Holkham’s regenerative agriculture approach is one that the original Coke of Norfolk himself would have recognised: crop rotation to prevent the draining of soil’s goodness by the repetitive planting of the same crops.

‘We have a much wider rotation now,’ says Leicester. ‘Coke of Norfolk had his four-course rotation 200 years ago. We now run a six-course rotation.’ He rattles them off: ‘It’s a cereal, beets, cereal, rape, a cereal, potatoes, and then we also throw some maize in there for anaerobic digestion.’ (The estate supplies gas to 2,500 nearby homes from maize and rye grass fed into the digestion plant, which was installed in 2014.)

Leicester adds thoughtfully: ‘We’re not being clever. We’re just going back to what my four-great-grandfather did 250 years ago in the agricultural revolution.’ This makes me wonder where we went wrong with farming.

The earl is unequivocal: ‘The Common Agricultural Policy was an absolute environmental disaster. Effectively you had civil servants decreeing what you as a farmer grew and you just followed the subsidies. And farms became subsidy junkies.’

Brexit has encouraged British farmers to promote biodiversity

With Britain’s departure from the EU, a new relationship between farms and the public purse is being established, one where, in Britain at least, farmers will be rewarded for promoting biodiversity and soil health as outlined in the 2020 Agriculture Act.

Much of the new regime appears to cohere with precisely what Lord Leicester has been doing at Holkham. I ask him whether he sees himself inspiring or being part of a new agricultural revolution, in the example of his great-great-great-great-grandfather?

‘There are farmers ahead of us,’ he says, ‘but we are big. We can hopefully bring a lot of influence to bear – so hopefully we can encourage others to go down this regenerative route and some already are.’

And, like his illustrious agricultural forebear, he is also considering writing new stipulations into leases for adopting the tenets of regenerative farming. In 2014 the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation warned that because of the depletion of soils by intensive agriculture we might only have 60 years’ worth of topsoil left – meaning humanity is facing disaster.

Leicester recognises the threat but is optimistic about the fate of his soils at Holkham: ‘Some people are saying there are 60 harvests left,’ says the earl. ‘We’ve got thousands of harvests left if we keep doing what we’re doing because we’re improving the soil. And in so doing we’re also getting better yields.’

***

As the earl and I head outside to meet the photographer and his assistant, who are waiting beside the lake to take his portrait, I ask how long the parkland has been arranged the way it is now. ‘Oh, about 200 years,’ he replies.

After the shoot I ask him how he describes himself: what does he do? ‘I say “farmer”, probably. You know, “landowner” sounds a bit pejorative in the 21st century. Or actually “businessman” – that’s what I am.’

This spurs another thought about being the 8th earl as we climb into the car. ‘It’s an immense privilege but you have a lot of responsibility,’ he says. ‘I’m not sure that’s something Meghan Markle understood.’

After the photographs outside, we all drive back to the house for another shot. This one is in the red-walled Landscape Room, which was rehung by Leicester’s father to conform with the 18th-century inventory.

Several Claudes compete for our attention alongside Poussins, Vernets and Giordianos. It’s a fitting place for a photograph to accompany an interview dedicated to the natural world.

While the photographer sets up his final shot, Leicester gives me a fast-paced tour of the stunning adjacent state rooms. We pause at a Gainsborough portrait of the 1st earl from 1775. It’s in a country setting and Coke of Norfolk is dressed in the clothes of a simple country squire, surrounded by liver and white spaniels.

‘My shooting dogs are still liver and white spaniels,’ says the earl with a smile. ‘People ask, “How long have you had them?” I say, “We’ve had them since the 1770s…”’