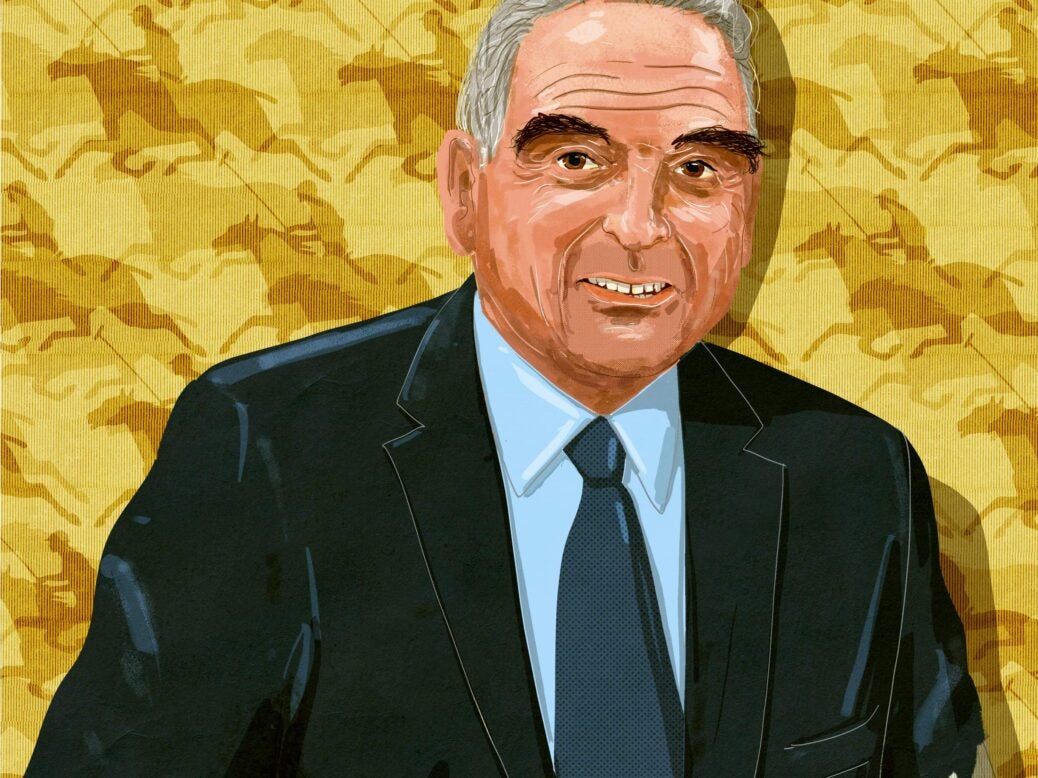

Having played a major role in the rise of wealth management, Spear’s Outstanding Achievement Award winner cautions on liquid assets, writes Christopher Silvester

Across the table from me are the two most rampant eyebrows in wealth management. They adorn the cheerful face of Michael Maslinski — veteran private banker, now a partner at family office services group Stonehage Fleming, and winner of last year’s Spear’s Outstanding Achievement Award. One eyebrow appears to be combed downwards, while the other is straining towards the heavens.

The effect is even more pronounced when he’s had a haircut and the eyebrows remain untrimmed, so Matthew Fleming, another partner at Stonehage Fleming, tells me.

I suspect Maslinski’s eyebrows are down to his Polish father, who came here in 1939 and joined British Army intelligence. He was based in the Rubens Hotel near Victoria. Maslinski’s mother was ‘very British’ and worked for MI6 until she was chucked out for allegedly fraternising with the enemy because someone went to her flat and saw a photograph of her previous boyfriend, an Austrian. ‘So I am this child of spooks, really,’ says Maslinski with a chuckle.

After his parents married, his mother helped the Polish Information Service. ‘They were very angry after the war, because of what happened to Poland and everything. My mother was furious, because to her the war had not been won.’

Born in 1953, Maslinski had four elder brothers, plus an adopted brother. ‘We were born and brought up in Hertfordshire, where my mother and her family had been for hundreds of years. I’m a Catholic and I went to St Edmund’s College in Hertfordshire, which was the oldest Catholic school in the country.’

His father had an estate agency in Belgravia and his mother didn’t go back to work until all her boys had grown up.

For his first proper job Maslinski joined Coutts, where he first discovered private client work. ‘They understood what serving clients was all about. They probably didn’t make enough money out of them, but they did understand it in a way in which, frankly, people struggle to do today. In fact, we called them customers in those days. Lawyers had clients, but banking was a trade and so you had customers. I spent 22 years there in all, and they were enlightened enough to encourage my more creative instincts and to tolerate my continual wish to challenge the system, often causing a lot of trouble in the process.’ They even allowed him a year off on full salary to do an MBA at Cass Business School at a time when the MBA was still virtually unknown in the UK.

‘Coutts in those days was a bank,’ he explains. ‘We didn’t call it a private bank. It was a bank that served the top end of the market, both corporate and personal. Most of our money was made out of corporate business and we had the accounts of some of the finest institutions in the City and blue-chip companies. Later, NatWest wanted us to focus more on private business, and yet the business infrastructure had been built up to serve the corporate world, so the transition was quite a tough one.

‘But suddenly the world woke up and decided that private banking was important. This was largely driven by the fact that all the retail banks or, as we then called them, the clearing banks, had gone for the mass market, where everything was about process. There was a need to segregate off their best customers, who needed and merited more attention because of their value as individuals, but also because they often owned businesses which banked with us.’

In 1994 Maslinski left Coutts to start his own business, advising banks across the world on how to set up private banking activities. ‘Because it was treading into entirely new territory, there wasn’t anybody else making their living in the way that I was planning to make mine. Knowledge of private banking was not available from McKinsey’s or any of the classic management consultancies. In the first six months I earned practically nothing, but in the second six months, with a bit of luck, I earned more than I had earned at Coutts in the whole of the previous year.’

Maslinski and Co called themselves strategy and marketing consultants, with the emphasis on strategy. There wasn’t a standard blueprint for each institution trying to start something in this sector. It depended on who they were, what their client base was like, and what skills they could reasonably expect to attract. ‘Nearly all of them wanted to aim one level above the level at which they could sensibly be playing.’

At one stage he was dealing with around 50 banks, while another 200 banks came on his various workshops around the world, which he conducted with a former Midland banker called Peter Renn.

‘Within the first year I ran workshops all over the world — in London, in South Africa, in Singapore, in Miami. Each bank had a different position and you had to work out what was the right formula for them.’ These banks need to do certain things in order to gain the trust of private clients. ‘If you gain their trust, they’re likely to buy certain things from you, but if you abuse that trust then they jolly well won’t. And you’ve got to be offering them the right things at the right time in the right way. You’ve got to have a theory as to why people are going to want to come to you, and you’ve got to have something to say to the market.’

What struck Maslinski forcibly was that a lot of organisations tended to be driven by the wish to accumulate assets under management rather than the focus on personal service and the need to understand clients and provide them with better banking. ‘Most of these institutions were setting up private banks without really thinking the issue through fully. So I got involved with anybody dealing with private clients — asset management firms, law firms, accountancy firms — and advised them about how to serve their private clients better.’

The term ‘wealth management’ came along towards the end of the Nineties, but prior to that private banking clients didn’t want to be labelled as wealthy. ‘The industry keeps inventing new terms to make it sound like a better offering. Is it a better offering or is it just the same — a new label on old wine? But to me, moving to the term “wealth management” from “portfolio management” or “investment management” meant that you were taking a much broader approach, looking across the total wealth of individuals, and probably at the family and their overall circumstances as well.

‘A lot of people who have used the term “wealth management” are most certainly not doing that: they’re looking purely at the liquid assets, and the liquid assets are the easy bit, really. There’s much more to wealth management than managing a pot of money to a brief. It means getting involved in and understanding and advising on the wider assets, which, in our case, is often family businesses and things of that kind, but also multiple other sorts of ventures — art collections and philanthropic stuff. We’re in the game of long-term wealth management across the generations. And the way that you do that cross-generational bit has a direct impact upon the way you actually manage the assets, because you’ve got to keep shifting what the assets are to suit the next generation, and you’ve got to manage that transition from one generation that has a particular set of attitudes and preferences and attitudes to risk to another generation that thinks in a different way.

‘I was always very much taken by serving the business-owners end of the market, probably because I’d had a corporate banking and corporate finance background to some extent myself. I knew that wealthy people — the really wealthy people — were involved in much more than just the management of liquid assets and share portfolios. And so I found that more at the family-office end of the market, working for individual family offices and multi-family offices.’

Most family offices were quite small boutiques, so there was a limit to how far they could go. There weren’t that many with a staff of more than 50 people. Maslinski had felt for a long time that there was ‘a huge opportunity among the more complicated, wealthier families with illiquid assets, with their own businesses, and with different business interests spread across different jurisdictions’.

Stonehage became a strategic consulting client of Maslinski & Co in 1997. It was then less than one tenth of its current size and was Maslinski’s smallest client. The firm asked Maslinski to become a director in 2011 and since then he has been working there three days a week.

‘It was a big step for me to scale back my other consulting activities, which had given me such an enjoyable, fulfilling and independent business life for over seventeen years,’ he recalls. ‘But of all the clients I had dealt with, big and small, Stonehage was clearly the one best positioned and most motivated to address the obvious gap in the market in serving the needs of wealthy, international, business-owning families. The opportunity to cap my career by playing a more hands-on role in a firm committed to changing the sector was too compelling to resist. I helped them to diversify the business internationally, to diversify the range of offerings, and to help build the brand.’

Since Robert Fleming & Co had also been a client of Maslinski & Co, he was ideally placed to introduce the two firms, which merged in 2015.

‘It is not an easy thing to give this sort of total service to very wealthy families, because the range of expertise that you’ve got to deliver means that you’ve got to carry quite a lot of different business units, each of which need a certain scale, but on the other hand you don’t want an organisation that’s too big, because the whole thing relies on these people working closely together.’

With about 500 people in eight jurisdictions, Stonehage Fleming has about 250 substantial clients (out of roughly 800 in all). They often come to the firm when they are contemplating selling their core family businesses, but they will also often have money invested in a lot of other businesses.

‘The entrepreneur has a fundamentally opposite view of risk management to that of the investment manager,’ Maslinksi points out. ‘The entrepreneur mitigates risk by concentrating on areas that he understands, while the investment manager mitigates risk by diversifing his investments.’

Maslinski still does some consulting for other clients, but this has been much scaled back, partly because of his wife’s ill health (she has advanced dementia). Outside his business life, his passions are rugby, polo and sailing. He has been a committed polo player for around 30 years, playing what he likes to call ‘country polo’, which is a world away from celebrity events. ‘One of my former rugby mates took me and put me on a horse and I found myself going round a cross-country course. So he decided I could ride. The next time he took me out he put a stick in my hand and told me to go and hit the balls!’

He plays in Hertfordshire at Silver Leys Polo Club, the oldest in the country. ‘I used to play religiously every weekend and travel the country and pay professionals to play with me, but now I do it fairly casually.’ Even so, he had his second hip replacement done in December so that he can be ready for the 2017 polo season. ‘For somebody who used to play rugby, it’s a great sport, because it’s very physical but you’ve got something else to do the running for you.’

Otherwise, for several years Maslinski was actively involved with a charity, WAM Foundation, that sent young musicians out to India to teach in schools there. He also inherited various trusteeships for charities from the Coutts family.

Looking back over his career to date, he believes that the wealth management industry has much further to go in its development.

‘It’s pretty awful that so many private banks have been done for mis-selling,’ he says. ‘But then private banking is excessively focused on liquid assets. To me, it’s disappointing that they haven’t embraced that wider context of wealth. Dealing with the liquid assets in isolation, you’re missing a trick from the perspective of the family, because the understanding of the wider affairs impacts on the way the liquid assets should get managed, especially if you’ve got businesses that are continually changing. And I think that the level of relationship management is still too superficial. There’s a lot still to come in terms of that depth of understanding and the depth of forging relationships with the different generations — understanding the family dynamics, being able to get people to address the hard issues, which are not just financial or technical issues, they’re often deeply personal issues.

‘I think that we’re now, therefore, moving into a new phase, and I sense that deeply. There is going to be a more family-centric approach. Organisations are going to realise that and put much more resources towards developing the skillsets — the interpersonal skills, what they call the soft skills, but they’re much tougher than actually the understanding of the product. There’s a recognition as well that much of the wealth management offering in the field of liquid assets is commoditised, that pricing is going to be under threat, and that only those who actually succeed in engaging on this much deeper basis are going to actually be able to add value, for which they can charge a lot. Other people will simply have to focus on making sure that they are very cost-efficient, technology-driven providers.’

While the growth of the industry has been ‘hugely satisfactory and pleasing’ to Maslinski, and he is happy to have played a part in that growth, nonetheless he thinks that ‘we’re just now moving into a new phase, where you are actually helping your

clients to make their own decisions as opposed to just giving them recommendations. And actually, that’s more difficult — and more useful. It’s been proven in management consultancy that asking good questions is better than trying to give answers, and it’s the same in wealth management. Because you’re helping people to think things through, as individuals and as families.’