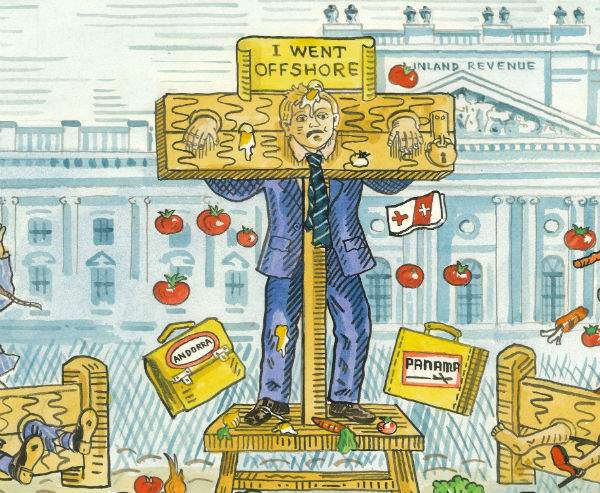

Until recently the wealthy could stash their cash offshore with impunity. Now, amid public resentment, they and their favoured havens are having to embrace transparency, says Alec Marsh

For somerset maugham Monaco was ‘the sunny place for shady people’. Panama, meanwhile – well before it became notorious for the leak of financial papers in 2016 – was very much on the same page. ‘Why can’t Panama invest in Panama?’ complains one of John Le Carré’s characters in The Tailor of Panama. ‘We’re rich enough. We’ve got 107 banks in this town alone, don’t we? Why can’t we use our own drug money to build our own factories and hospitals?’

Indeed, long before Mossack Fonseca was on the lips of every Guardian reader, offshore had garnered a reputation for clandestine financial shenanigans that in many respects it still struggles to shrug off. Where, after all, do John Grisham’s crooked Memphis lawyers go to launder mafia money in The Firm? The idyllic Cayman Islands, of course, the tiny British colony which since the 1960s has emerged as a major offshore, or international financial centre (IFC).

Cayman is but one of many IFCs of British origin: their number includes the British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. The French, meanwhile, need only drive into Monaco, and the Germans have Switzerland conveniently located and tolerated for many of the same reasons. All told, centres such as these are thought to hold £13-20 trillion. At the upper end, that’s equivalent to a third of global GDP in a given year, and twice the amount of wealth held in private hands in the UK.

That’s undeniably a lot of dosh. What’s also undeniable is the strength of public opinion which over the past decade has changed markedly. It had changed before the Guardian got its hands on the Panama Papers; it was changing already by the time the world saw footage of bankers streaming out of the offices of Lehman Brothers carrying cardboard boxes in 2008.

And that it has changed cannot be doubted: the Panama Papers achieved what Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband couldn’t – they materially damaged the then prime minister David Cameron’s standing in the court of public opinion. For a mass of the populace – many of whom would later vote against the expressed wishes of Mr Cameron by choosing to exit the EU – the details of his father’s offshore financial arrangements and the small benefit accrued to him nailed the coffin firmly shut on his credibility.

That it wasn’t a fair judgement doesn’t come into it. Don’t forget what Theresa May said when she arrived at Number 10, after her bloodless putsch in the Conservative Party. ‘Too many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass on the street,’ she said pointedly. ‘But if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.’ Likewise, much of the public vitriol poured on Donald Trump relates to his tax affairs – and his frankly odious claim that not paying tax made him ‘smart’.

‘It’s amazing how things have changed,’ remarks top tax accountant Ben Grist of Dixon Wilson. ‘Tax legislation is more of a headline these days – 10, 20 years ago we never had news stories or articles about tax.’ As a result, clients are clamouring to pay their way, because no one wants to end up in the papers: ‘Ten years ago, if I said to clients: “Your tax bill wasn’t zero,” they’d have fired me,’ says David Kilshaw, private client partner at EY. Now the reverse is true. ‘The “Daily Mail test” has definitely gone into the tax lexicon,’ concedes Kilshaw, who likens the change of attitudes to the smoking ban – would you light up now in your favourite restaurant?

The profession is changing, too, as the stars of our tax advisers index (page 65) show. Rachel Bentley, director of PwC’s private client team, says that in the aftermath of the two principal global reporting standards measures – FATCA and the CRS – that more clients are looking to adopt voluntary disclosure programmes. ‘We are in a world that is ever-changing, and we can’t just look at the tax aspects,’ says Bentley. ‘We have to take a broader view.’

One who does just that is the eminent lawyer and homme d’affaires par excellence, Mark Stephens of Howard Kennedy. For him there’s no question that offshore has become a dirty word. ‘It’s got to the point where there’s an assumption that you’ve done something wrong or are doing something wrong if it’s offshore,’ the flamboyant solicitor, whose clients have included Julian Assange, tells me. ‘And there’s a reputational hit – and you have to justify why you’ve got the stuff offshore, if you’re going to.’

While Stephens thinks most IFCs have cleaned up their acts, because of either direct foreign oversight or the desire to avoid legislation, the fact remains that public opinion is more fixated on the issue of taxation. Ultimately, his point is, if you’re clever or rich enough to avoid paying tax, you’re seen as shifting it on to others. ‘That’s why there’s a social stigma attached to shifting that burden,’ he adds. ‘So the Daily Mail reader is not going to think you are clever if you avoid paying tax – whether you’re a corporation or UHNW – they’re going to think, “I’m paying for that person, I’m subsidising that person, and they’re much more wealthy than I am.”’

So what’s the answer? ‘The clients that I have had who pay their full tax burden and are UHNWs are probably in the best moral position – they can’t be criticised,’ notes Stephens. ‘That’s why Paul McCartney has never been criticised, why Ringo Starr has never been criticised – because they pay their full weight; and [it’s why] my British politicians want to pay what’s right, so they can’t be subject to this false allegation that they’re not paying their full weight.’

One area where Stephens favours going offshore is for protecting privacy – though he remarks that it’s ‘flipping difficult’ to set up such a structure for a client who might also stipulate their desire to pay their full marginal rate of tax.

But what of an UNHW’s right to determine where he or she lives and pay their tax accordingly? One staunch defender of this right is the prominent tax lawyer James Quarmby, who notably took John Humphrys to task on Radio 4’s Today and dismisses much of what is written about tax havens and trusts as a ‘fairy tale’.

‘I think it’s good that people have choices because if a country puts tax up too high, hopefully they will leave the country and the country in question will realise that economic theory dictates that if you put up taxes too high, your tax take goes down,’ Quarmby notes. ‘If someone wants to move their home and family away from the UK to another country to pay less tax, good luck to them. They can’t come back; they can’t abuse the system.’

So where would he go? None of the locations is what we would regard as a traditional offshore location. He cites Hong Kong, with income tax of 13 per cent, or one of a handful of EU states such as Estonia, where it is 20 per cent. Or how do you like the sound of Malaysia? It has an ‘almost colonial tax system which basically says if you don’t have your assets in Malaysia you’re not taxed,’ Quarmby declares. ‘So if you’re a wealthy Malaysian, you bank in Singapore and that’s the extent of your tax planning.’ He concludes: ‘There are dozens of places I could mention where they’re not going to tax you if you’re a wealthy, capital-rich person – but you will not be moving to Cayman. People don’t. It’s boring. It’s a sandy pancake in the middle of the Caribbean. The idea that tax havens are places people move to to avoid tax is just wrong. Rich people want to be connected; they want to be in hubs. Guernsey’s not a hub: there’s only one airline and if that goes down you’re trapped, you have to get a ferry.’

Put like that, it’s not such an attractive proposition, but for corporates and hedge funds, as well as rich individuals, IFCs have an important role to play, whether it’s by protecting privacy or by providing an even and mutually agreeable playing field for globally dispersed investors to locate a holding company. ‘The result of those IFCs doing what they do increases economic activity and the tax in the countries in which you live, and therefore reduces your own tax bill,’ says Quarmby, ‘because if we have a wider tax base the amount of tax each citizen has to pay goes down.’

The best part of 5,000 miles away, in the Caribbean island of Grand Cayman where John Grisham set his bestselling story of offshore corruption, they take the view that ‘not all IFCs are created equal’. Cayman Finance’s CEO Jude Scott insists that it’s a ‘transparent, tax-neutral jurisdiction that is also a strong partner in combating global financial crime’ and has a ‘track record of meeting or exceeding global regulatory standards for anti-money laundering, countering the financing of terrorism, and tax matters’.

Certainly it’s among the tier of IFCs that are signed up to the CRS, so it will be reporting on accounts held to the UK authorities. ‘In the post-Panama Papers world, we’re seeing a “flight to quality”,’ says Scott. ‘Investors are moving away from less transparent jurisdictions and moving toward those like the Cayman Islands, which has developed its tax system in a consistent, predictable and globally responsible manner that supports the efficient free flow of goods, services and capital between countries and parties around the world.’

Back on this side of the Atlantic, over breakfast, the quietly spoken David Kilshaw strikes a more emollient tone, one even to mollify the demotic, self-appointed guardians of public good at the Daily Mail. ‘The word “offshore” can be emotive,’ he concedes. ‘But I’m absolutely convinced [that] putting stuff outside your territory of residence is absolutely fine, as long as you can follow the rules and do it properly. Maybe we need to come up with a different word.’

With growing transparency he thinks ‘the barometer will swing back again’. ‘It’s not so much offshore,’ asserts Kilshaw, ‘it’s the fact that when you see the word “offshore”, it’s so hidden behind smoke – it’s almost like “cinema vision” of tax planning. Offshore should be upfront and stand for quality administration, quality disclosure. There’s so much skill in places like the Channel Islands that can be brought to the fore.’

This feature first appeared in the September/October issue of Spear’s which is available at your nearest WHSmiths travel store or independent news agent. To subscribe, visit www.spearswms.com/subscribe