Who’d like to shoot Charlie Brooker in the testicles? Bizarrely, a new video game offers players the opportunity to do just that. Of course, that’s not precisely how the PR campaign for Sniper Elite III expresses it. They say only: ‘Gamers get the chance to shoot the polarising Charlie Brooker in Sniper Elite III.’

But anyone who’s familiar with the Sniper Elite series of games will know that their unique selling point is the special KillCam. Every time your character successfully snipes an enemy, the action slows and a 3D x-ray shows the bullet shattering bone and mashing soft tissue in glorious HD. You can well imagine the shot prized by aficionados.

So this is what Mr Brooker — a fine comic writer, computer game enthusiast and professional curmudgeon — was offering well-wishers when he accepted a walk-on role as a German field officer (he follows Hitler around saluting). We tend to say, when a real human being appears in a work of art, that they have been ‘immortalised’. It doesn’t quite seem the right word here, given that Brooker’s character is there to be killed over and over again. Mortalised, perhaps. But if the format is somewhat different, the substance remains the same.

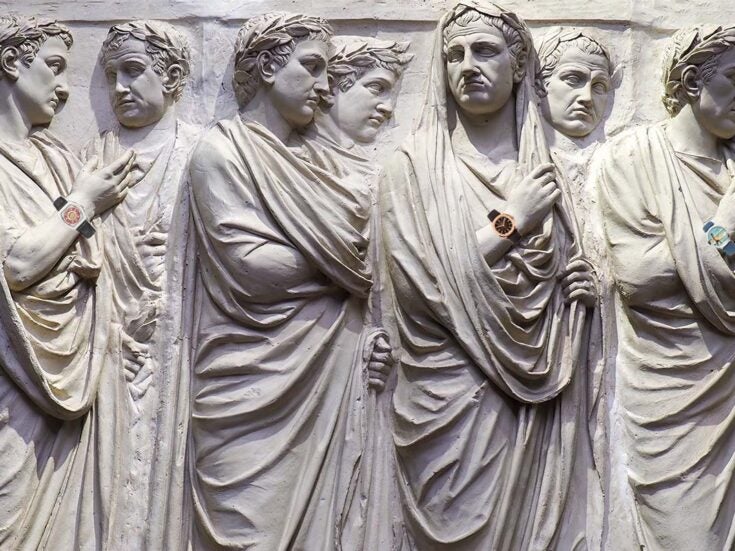

To appear in a work of art has always been a considerable status symbol. The houses of the wealthy and the powerful have long been hung with their likenesses, and we would not all be so intimately familiar with the creepy droop of the Habsburg lip had they not.

A patron might frequently appear, too, in the crowd scene of some iconic tableau, not just in a portrait. In the literature of the Renaissance, where poetry and drama were involved with networks of flattery and patronage, the same applied: the mighty were dedicatees of works of art, enjoying the occasional walk-on.

The celebrity guest appearance in a video game — Jonathan Ross has a voice cameo in Halo 3 — is simply a next-generation equivalent of the same thing. It’s only going to continue as the technology develops. Celebrities are invited to appear in video games as treats for the fans.

Let’s put aside for a moment the appearance of real people in works of art as satire or revenge (the roman à clef) or as a private joke (Enigma Variations; The Waves). What’s perhaps happening is that the distinction between appearing in art as a dispassionate mark of honour and appearing as a result of direct patronage or cash exchange — hitherto fuzzy — is becoming a little clearer. Ross and Brooker won’t have paid to be included, but others soon might.

Is it unthinkable that — as with the patrons of Renaissance painters — the creep of product-placement into games and Hollywood films might have its terminus in a sort of person-placement? All it will take is an enterprising studio and an HNW with the thought that an ideal birthday present for his teenage son might be to appear as a Space Marine in the next iteration of his favourite shoot-em-up.

In literature, it’s already happening. Fay Weldon’s novel The Bulgari Connection broke ground in 2001 when its author accepted £18,000 from the jeweller to include at least twelve mentions of the brand. (She managed 34.) In 2005 several authors, including Neil Gaiman, Stephen King, Dave Eggers and Rick Moody, held an online charity auction offering bidders the chance to appear as a character in one of their stories. This is now becoming as much a staple of the Cotswold fundraiser as the gift box from Jo Malone.

The problem is, of course, that the easier it gets the less exclusive it is. You can now star in a ‘personalised’ copy of Pride and Prejudice — your name inserted by algorithm and the book printed on demand — for twenty quid, if you really must. What, in an age where works of art are distinctly more flexible than oil paint on canvas, can be banked on, long-term, to impress?

‘As Himself’ on the end credits of a Hollywood film: that will probably still have the requisite gasp-factor. A cameo in the boxed release of a triple-A video game likewise; downloadable content less so. And as far as appearing in a book goes, the prestige and perceived high-mindedness of the author is the thing: Kathy Lette, OK; Fay Weldon, better; Hilary Mantel, pretty impressive.

By the cameos real people play in works of art shall ye know them — their wealth, status and (when it’s them making the work of art) relationships with themselves. As Andrew Graham-Dixon’s fine biography points out, Caravaggio frequently painted himself into his work. One version of his David with the Head of Goliath is widely held to be a double-self-portrait: the young Caravaggio pictured holding the severed head of the adult Caravaggio. Which, on a scale from nought to ‘that’s messed up’, puts volunteering to have your clockweights shot off as a video-game Nazi into some sort of perspective.